Lucasfilm and Tippett Studio: A 10-Year Collaboration Built on Legacy

Stop-motion animation artists share insights about a decade of Star Wars projects made in partnership with Lucasfilm and Industrial Light & Magic going back to Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

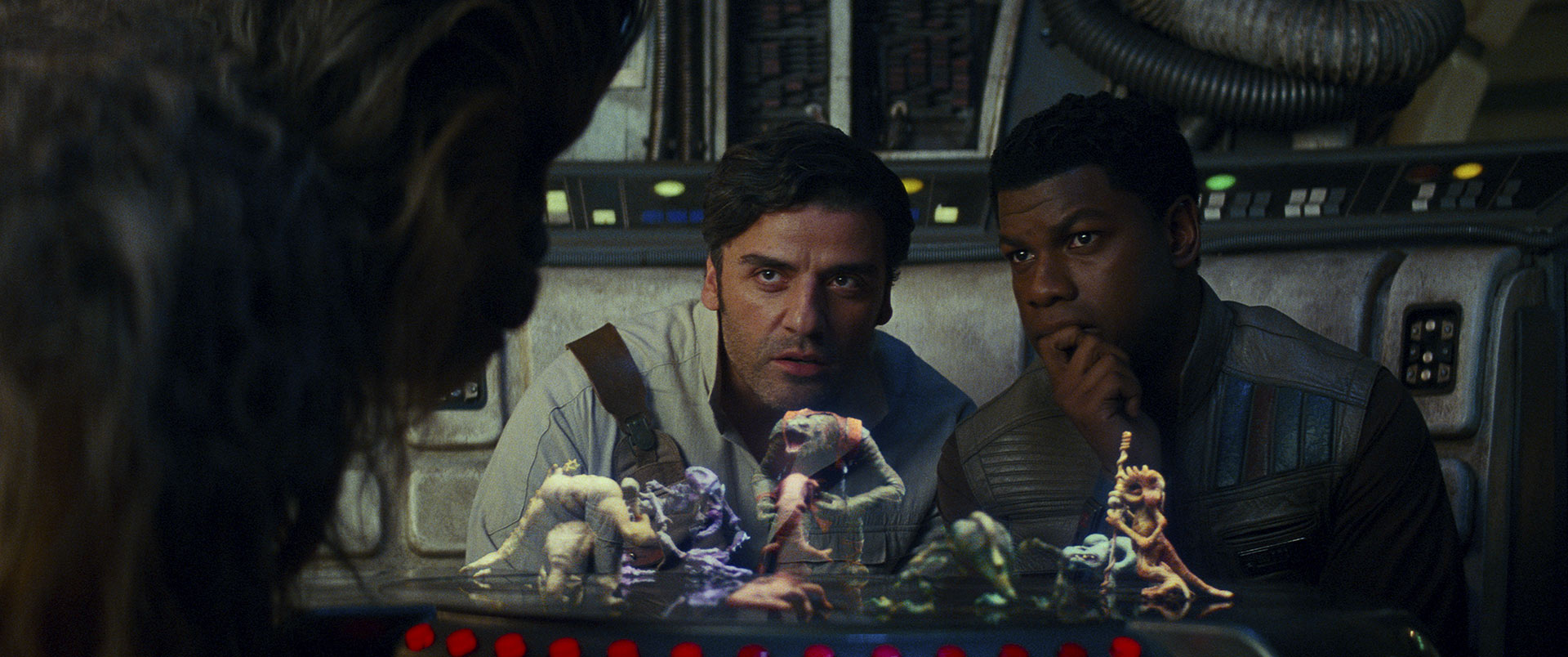

Like many in his generation, stop-motion animator Tom “Gibby” Gibbons took inspiration for his ultimate career when he saw Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) as a child. Unlike his peers however, one very particular sequence became his obsession: the dejarik holochess monsters. Little did he know that nearly 40 years later, he’d be among the artists to work on the revival of the sequence for Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015).

“How weird is it that I got to work on this?” Gibbons says with a laugh. “It was probably one of the weirdest synchronicities, cosmic accidents, that’s ever happened in my life — that I had that relationship with the chess set as a kid, and decades later I got to animate it.”

Growing up loving the films of Ray Harryhausen, the original holochess sequence from Star Wars had an outsized impact on Gibbons. “There had been a gap in films where I hadn’t seen the things I particularly loved in them — puppets and monsters — for a while,” he recalls. “Then Star Wars came out and the chess set appeared. That was the moment when I decided I wanted to do that. I realized there must be new people doing this kind of work. It’s still a thing.”

Enter artists Phil Tippett and Jon Berg. Originally hired at Lucasfilm’s Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) to help make creatures for the Mos Eisley Cantina, Tippett and Berg convinced director George Lucas to use stop-motion animation to shoot the holochess sequence. They made ten distinct monster puppets, eight of which were used, and shot the sequence with the assistance of Dennis Muren as camera operator.

This all-too-brief moment in the original Star Wars film heralded a renaissance in the use of stop-motion for visual effects, much of which was centered on the work of Tippett and his colleagues at ILM on productions like Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Dragonslayer (1981), and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984). By the mid-1980s, Phil Tippett had departed Lucasfilm to establish his own Tippett Studio in nearby Berkeley, California. Stop-motion remained an important stock-in-trade for many years on visual effects projects like RoboCop (1987) and Willow (1988).

As computer graphics (CG) heralded yet another renaissance in the industry, Tippett Studio embraced the change, often working in collaboration with ILM on visual effects projects. Among their animation talent was Gibbons, who’d broken into the industry in the San Francisco Bay Area as a stop-motion animator before learning CG animation. He never stopped working on stop-motion projects, however, and it came as quite a surprise in 2014 when he was told that Lucasfilm had approached Tippett Studio with an unusual request: could they recreate the original holochess sequence with new stop-motion animation for the forthcoming Star Wars: The Force Awakens?

What might’ve seemed like a relatively small request at the time ultimately blossomed into what is now a decade-long collaboration between Lucasfilm, ILM, and Tippett Studio on multiple Star Wars features, The Mandalorian (2019-23), The Book of Boba Fett (2021-22), and most recently, Star Wars: Skeleton Crew (2024-25), which has been nominated for 17 Children’s & Family Emmy Awards. In September, the studio hinted at a return to the galaxy far, far away, contributing to The Mandalorian and Grogu, which will premiere in theaters May 22, 2026.

A Holochess Trilogy

As work was beginning on The Force Awakens, which marks its 10th anniversary this month, a number of Tippett Studio’s CG artists had convinced Phil Tippett to let them provide assistance on his personal stop-motion opus, Mad God (2022), with the use of new digital cameras and related tools. Among them were visual effects supervisor Chris “CMo” Morley and lead fabricator and art director Mark Dubeau. “At the places where I’d worked previously, it was very ‘stay in your lane,’” explains Dubeau, who’d started his career in animation and visual effects in his native Canada. “At Tippett things were more open, and a lot of that had to do with their background of doing practical work, with people pitching in together. Even in CG, they wanted people who were characters, who had different types of skills and experience.”

“Learning the stop-motion craft was something I always wanted to do but never got to,” explains Morley, who studied traditional fine arts in San Francisco before becoming a CG artist. “The first shot we did for Mad God was hand-cranked on a model mover. We now use a motion-control camera with animated lights and all these different elements. A lot of people sparked their own stop-motion careers on Mad God. By the time Lucasfilm and J.J. Abrams were making The Force Awakens and wanted to do practical effects, it was a feeling of, ‘We know how to do that.’ That was our first resurgence of stop-motion.”

Dubeau was largely responsible for organizing the team that would create the puppets themselves. “We looked internally, and collected everybody we knew who had the abilities to do this kind of work,” he explains. “When we needed additional help, I recruited fabricator Frank Ippolito, and Phil still knew a lot of people in the community, and that’s how someone like Brett Foxwell came in.”

Machinist and engineer Brett Foxwell had started making stop-motion puppets and related equipment while employed in a machine shop for Northwestern University’s medical school. Moving to California, he found work with stop-motion armature maker Merrick Cheney, who’d worked previously with Phil Tippett. Foxwell soon became another member of the Mad God crew, and after a stint at Laika on Boxtrolls (2014), he returned to Tippett Studio just in time for the holochess sequence.

“We went to the Skywalker Ranch archive and looked at the original chess pieces, which were in pretty bad shape,” Foxwell recalls. “They’re latex, which degrades badly. We took pictures and looked closely at the miniatures, all the while glancing over at the racks of other stuff that extend back into the room. After we were done, the curators said, ‘Go help yourself.’ We explored all throughout that space looking at everything. Phil’s shop is the same way, going back to the 1980s, including the machines themselves, which they used for RoboCop and the first Jurassic Park [1993] dinosaurs.

“I looked up the canon for the two biggest chess characters,” Foxwell continues, “the Mantellian Savrip and the Kintan Strider. Phil never paid much attention to the canonical names. For him they were Mr. Big and Hunk. The Kintan Strider, the smaller of the two, never had an armature. The bigger one did have an armature, which Phil had made in high school. The old latex had been stripped off of it, so I was able to look at it. It was very roughly made out of bicycle chain links and chunks of metal. I asked Phil what the new puppets would be doing and what quality they needed to be. He said, ‘We don’t know what they’re doing yet. Make it a good, high-end armature that can do anything.’ It was a wonderful challenge to rebuild the puppets in the best forms I could.”

What the puppets actually did was determined by the story beats of the sequence, which Lucasfilm allowed Tippett’s crew to pitch themselves. “We saw each of the sequences as an opportunity to tell a little story on a smaller scale,” notes Mark Dubeau. “We try to make sure that things have a sense of history and fit into that world.”

“We had to understand where this fell in the timeline,” notes Tom Gibbons, who animated the scene with Chuck Duke. “This was after what we’d seen in A New Hope. Had the game progressed? Had anyone turned it on since we’d last seen it? J.J. Abrams said no. So when it turned back on, we picked it up where it had left off. Mr. Big had just picked up and thrown Hunk onto the ground. Phil stepped in and said, ‘We’re going to reverse the action. This time, Hunk is going to win.’”

The result caused a stir amongst Star Wars and stop-motion fans alike. This led to additional scenes shot for both Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018) and Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker (2019). Solo in particular allowed for a playful bit of retroactive storytelling.

“One of the coolest things about doing stop-motion as a visual effect is the integration into the live-action plates,” explains Chris Morley. “Those are already shot, so we have the basic lighting there. We add little things, like rim lights, to take the creature into a more magical realm. The integration is really what I love. For the animator to see the plate where the creature will be integrated, with the actors in position, it allows them to play with that space and inject some more soul into it. It’s not being created in a vacuum.

“Shooting with these plates also allows for happy accidents and serendipity to take over,” Morley continues. “A perfect example is when we were working on Solo, there’s a scene when Chewbacca hits the dejarik table, and on set the actor [Joonas Suotamo] broke off two of the little red buttons. They had asked us if we might paint those two buttons back in, but it spurred the idea to treat that as a serendipitous event. Maybe because Lando’s ship is new, the dejarik table is fully operational at that stage and has ten characters instead of eight. So the two buttons that broke off during shooting were those two other characters who were never seen again. The original 1977 scene is the next time we see the holochess, and there’s only eight in that sequence.”

Famously, the crew decided to use two creature designs by Phil Tippett and Jon Berg that George Lucas had eliminated from the original scene in A New Hope, giving them their moment onscreen at long last.

A New Kind of Walker

“The Mandalorian was a real shot in the arm,” says Mark Dubeau. “For Phil and all of us, it had that shoot-from-the-hip feeling of the original Star Wars stories. It had a Wild West tone with these cool characters doing their thing. Phil enjoyed it so much that he tweeted about it, and that was noticed by people like [Lucasfilm executive design director] Doug Chiang, and they started coming to us with ideas.”

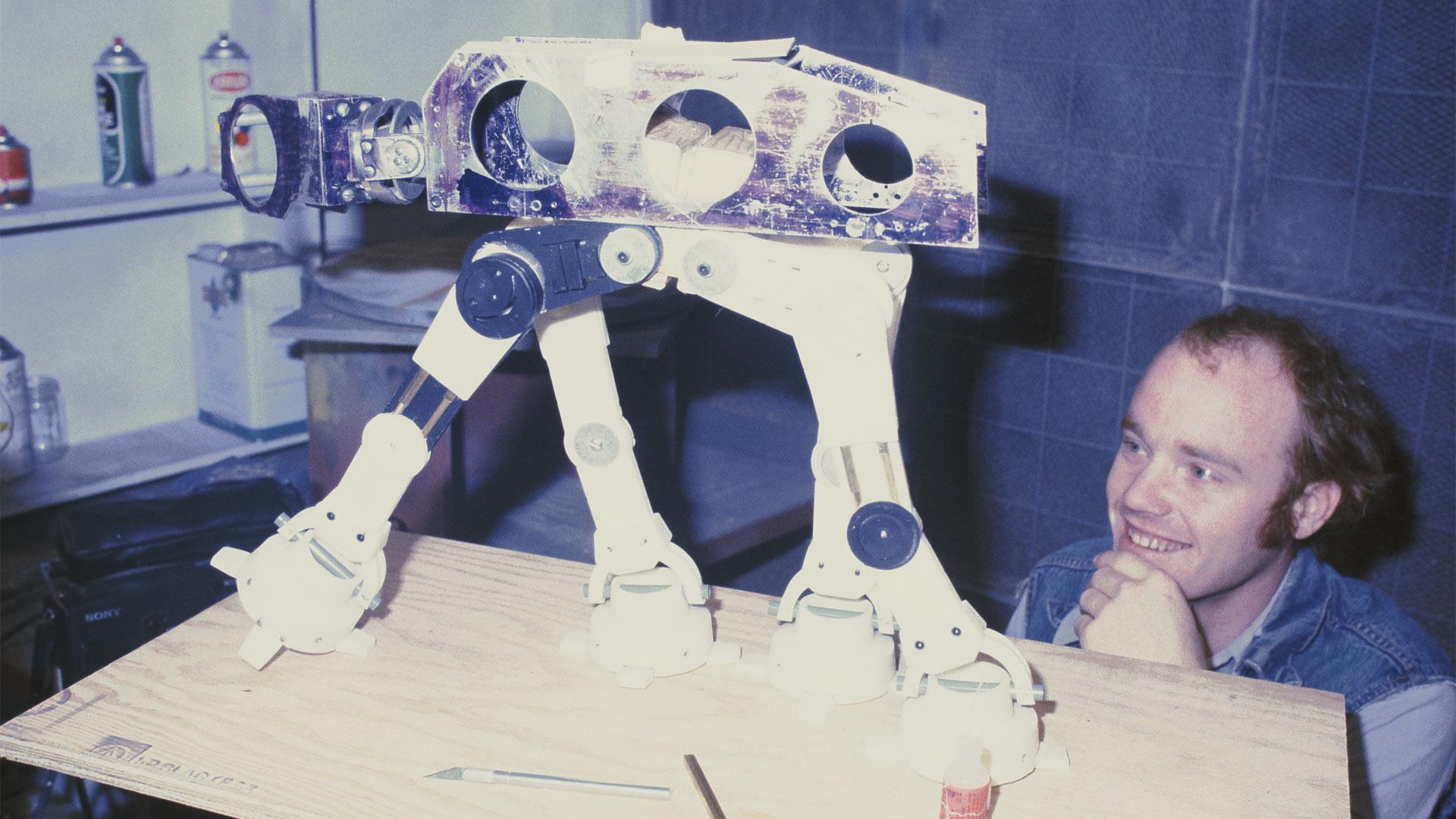

For The Mandalorian’s second season, showrunner Jon Favreau and Doug Chiang’s Lucasfilm Art Department had a vehicle in mind. “Doug and his team explained that it was like a probe droid and an AT-AT were combined,” Dubeau recalls. “I did three kit-bash designs in ZBrush and sent those to him. Doug took what he liked best out of all of them and asked for different adjustments. I detailed the model from there. Considering that Phil is known for the AT-ATs, I guess it’s only right that the first thing we did after the chess pieces was an AT-AT-style vehicle.”

Working on a short schedule, there was no time to build a full armature. Crew member Sean Charlesworth took the lead in 3D-printing the components, which were held together with washers and bolts at the various joints. Once Tom Gibbons and David Lauer began animating the puppet, they were surprised to discover that the heat of the stage lights caused it to sag. The animators would have to finish shots in their entirety in a single session.

“Psychologically, it’s more of a scientific approach with the walkers,” notes Gibbons. “We based them off the AT-ATs, and we were trying to get the same timing and feel. But I think it’s impossible to not anthropomorphize things as you’re animating them. I can definitely remember anthropomorphizing those things into big, weirdo elephants. The little claw that came off of the walker’s butt to pick up scrap moved around like a tail. Even though there were humans inside of it, driving it with intention, I can remember still having a specific feeling about the walker’s movement.”

Seen largely in the background during scenes in a scrapyard on the world of Karthon, the walkers lift fragments of Imperial TIE fighters with their claws. The Tippett crew shot the fighter pieces as separate elements, digitally compositing them with the walker puppet after the fact.

“That’s an example of using digital means to augment the stop-motion,” Chris Morley points out. “We don’t like to follow any strict rules. We’re not purists for stop-motion at all. If anything, we’re more like pirates. We want to make the coolest thing with the best possible technique, and everything’s on the board. We know the digital world inside and out and we know the stop-motion world inside and out as well.”

A Spider with Six Legs

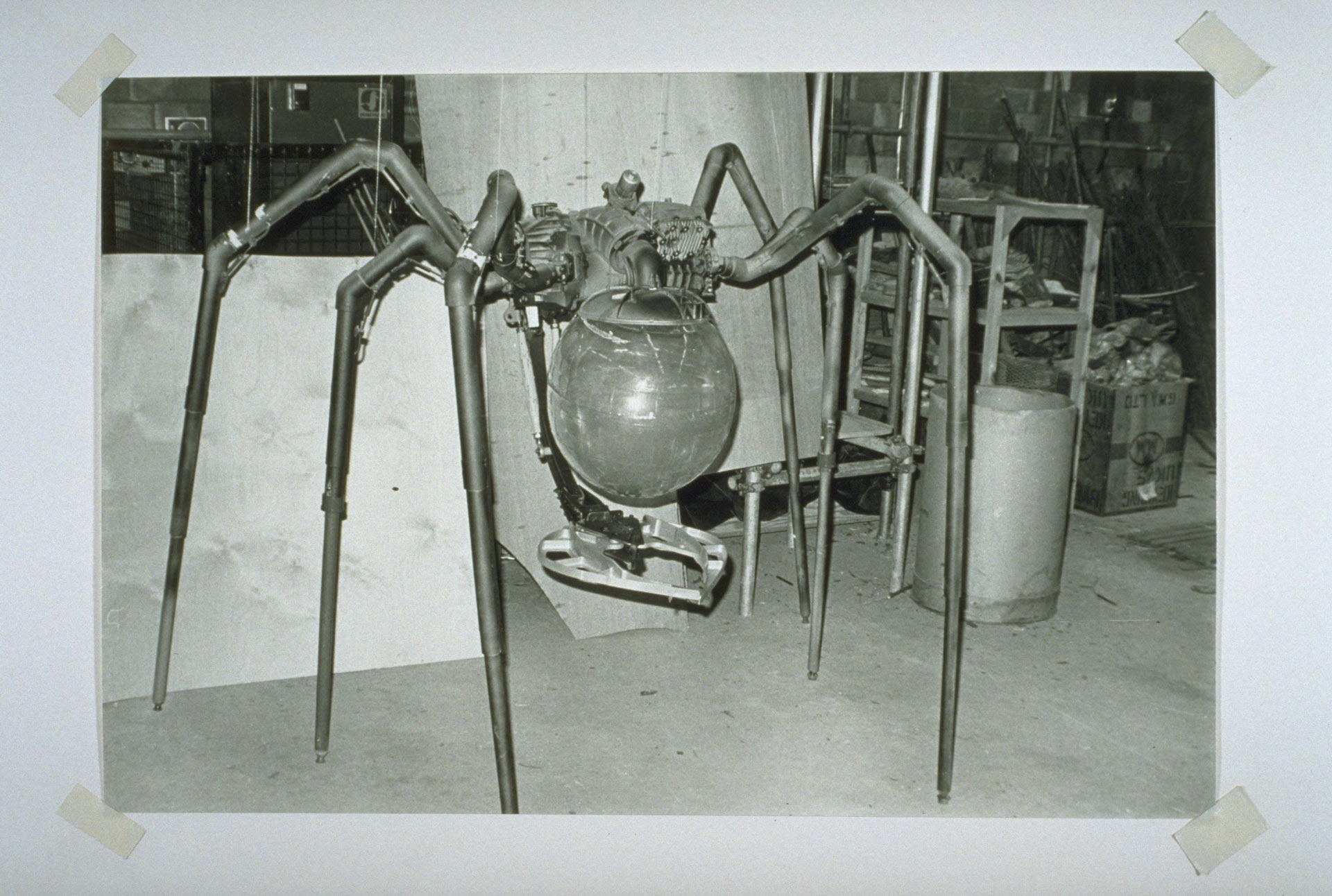

The Book of Boba Fett’s third episode opens with an establishing shot of Tatooine, which soon reveals the palace formerly belonging to Jabba the Hutt. In the foreground, a striking mechanical spider — first seen in the background of a shot in Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983) — scurries across the desert. These B’omarr monks, as they are known in the saga, are in fact the brains of devoted monastics kept alive in a ball of fluid in order to achieve a so-called heightened mental state.

If the lore seems complex, it pales in comparison with the character’s stop-motion puppet made by the Tippett crew. As Mark Dubeau points out, “The legs were the challenge from the get-go.” Sean Charlesworth again brought his 3D printing expertise to the challenge, identifying a process that allowed them to print components in metal. “It was the ‘A-ha!’ moment that allowed us to see how it would come together,” Dubeau adds.

“Sean designed and built the legs, which would be printed out oversized,” explains Brett Foxwell, “then I’d put them in the milling machine and trim them down to the right level of precision so the joints would function. It was difficult because the legs were so thin and small. If the spider was standing on all of them, they could hold it up fine, but when the spider was walking, you might only have three or four making contact at a time.”

The solution was to rig the puppet with a fishing line from above, which is often invisible to the camera, thus saving expensive paint-outs in post-production. “I had worked with a CG model to better understand what could be done or not done,” says Tom Gibbons. “When you get onto the set, however, you run into small issues with things like the terrain. There were moments where she couldn’t move forward at speed in a legitimate way, so I’d have to start picking legs up before they should start moving. There are certain cheats I know so that I can make the legs appear to be tied down, but they’re not. That allows me to keep moving her forward at speed. With the help of the fishing line, there are frames where all the legs came off the ground.”

The terrain over which the spider travels is the largest such construction the Tippett crew has built to date, some 20 feet of desert rock and sand at varying elevations. “Considering the interaction of light, it’s always best to have physical things there,” says Chris Morley. “You’ll get natural bounce from the ground plane up onto the creature, and you’ll get natural shadows. Because we know digital visual effects so well, we’re able to match the cameras and import that into the motion-control system. At certain points, all but one – maybe two – of the legs were off the ground.”

A Continuing Legacy…And More Monsters

CG modeler and fabricator John “JD” Daniel was equally inspired by his love of science as much as his love of art in pursuing his career path. Studying invertebrate zoology and marine biology in college, he became an intern at ILM’s Creature and Model Shop in the early 1990s, working as a mold maker and caster. Like many of his colleagues, he made the transition to CG work, ultimately leading him to his role at Tippett Studio. After helping fabricate the puppet for Pixar’s stop-motion short, Self (2024), he was recruited onto an exciting Star Wars assignment.

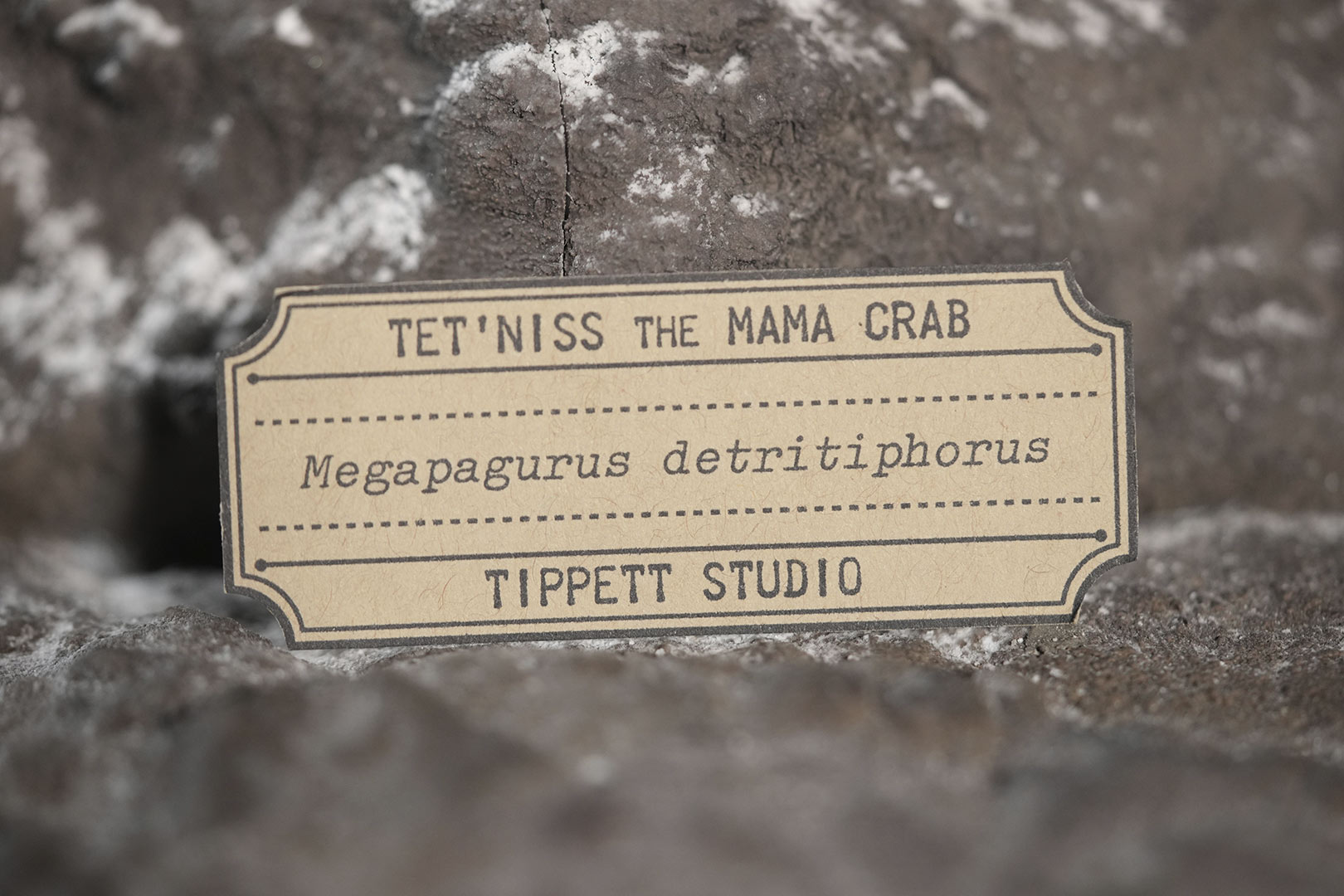

“Mark Dubeau was like, ‘You’re going to love this one,’” Daniel says in reference to the new creature for Star Wars: Skeleton Crew (2024-25). “We get to work on a giant crab? Sold.”

Known either as the “Trash Crab” or “Mama Crab” or even “Tet’niss” in reference to its many spiky protrusions, this puppet was “our first real attempt to do the old school Harryhausen approach but also integrate CG methodologies to help achieve a level of sophistication that you don’t often see in stop-motion visual effects,” Chris Morley notes.

“Having worked on stop-motion feature films at other studios, on that sort of project, everyone is in a specific department, and things are handed off,” explains Daniel. “One person sculpts the puppet, another makes the armature that goes into the puppet, someone models the plastic parts that attach to it, another person paints it, and someone else animates. It’s a waterfall approach, if you will. That’s not how the Tippett crew works. It’s more like a bunch of engineer-artisans getting together in a room trying to figure out how to launch a moon rocket. Rather than just handing an animator a puppet, we’re working with them directly to understand what it has to do and how we can make it work. There’s a lot of discussion and testing out ideas. Some of the best solutions have come from this iterative method of working. We’re all working back and forth with each other on different parts using both digital and practical tools. It’s a very small and intense way of puppet-building and doing stop-motion.

“I have such a deep love of Star Wars monsters and creatures,” Daniel adds. “There’s that wonderful thrill when you’re working on something that no one has seen yet, but they’re going to…one day! Knowing Mama Crab will be part of that world, hung up amongst the tauntauns and hammerheads and all kinds of strange creatures that I’ve loved ever since I was a kid.”

That legacy comes from Phil Tippett’s leadership, itself a part of Lucasfilm and ILM’s founding DNA. “What Phil really brings to it is a broader sense of storytelling,” says Mark Dubeau. “He makes us think about intention and what it means to the scene or sequence. With something like the trash crab, he made us look at the old Harryhausen sequences and think about where those performances originated in the story. Those are the great examples of the past, and we’re trying to find ways to wow people the same way those older sequences used to do.”

As Morley is keen to point out, this stop-motion work isn’t about novelty, nor is it principally derived from nostalgia. It’s about using another viable option in the visual effects toolset. “I want to bring it to another level,” he says. “I want to utilize digital technology to inform the stop-motion process. At the end of the day, whether you’re retiming stop-motion or adding digital elements on top of stop-motion, it still has that basis of human craftsmanship that I think we need to retain. Especially with everything going on with the advent of AI, keeping ties to the root of our craft is extremely important for me.

“There’s been a really nice arc with these Lucasfilm projects,” Morley concludes. “The amount of stop-motion in screen space has grown larger. Lucasfilm and ILM were very smart to start with something like the chess set, something that’s slightly mimicking an earlier example, but taking it to a new level. Then they move to a new kind of Imperial walker in the background. And after that, they bring it a little closer to the camera with the B’omarr monk spider. Then with Skeleton Crew we have a full-on creature. That progression has been treated with a lot of respect and intelligence on Lucasfilm’s part. We wouldn’t have been ready to go all out at the beginning. Now we are ready for anything.”

—

Lucas O. Seastrom is a contributing writer & historian for Lucasfilm.