Caves, Castles, and Tuna Factories: Inside the Locations of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny

From the streets of Morocco and Sicily to his own hometown, Duncan Broadfoot helped organize a global production.

One of the most logistically complex location shoots ever organized by Lucasfilm came in 2018, during production of Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker. The Wadi Rum region of Jordan stood in as the desert world of Pasaana, where an ancient festival brought hundreds of alien creatures together on a massive scale. To film the sequence, the production crew enlisted the Jordanian army for support, building roads and infrastructure in the blistering heat. For Scottish-born supervising location manager Duncan Broadfoot, this was his introduction to Lucasfilm, and seemed just the sort of experience required for a similar role on Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny.

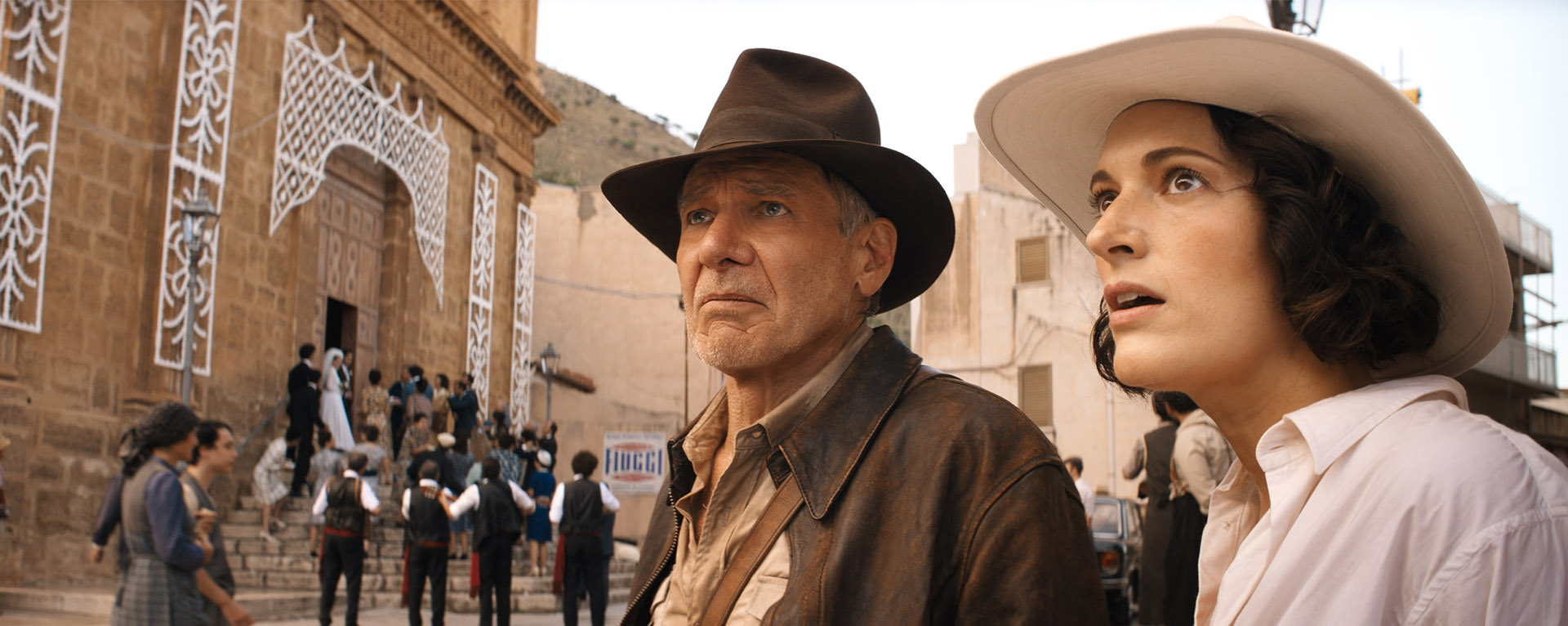

“I grew up watching Indy,” Broadfoot recalls. “As soon as he donned that leather jacket, hat, and whip, he become something other than a professor. This adventurer was very appealing to me as a young boy. I have vivid memories of watching the movies.” Growing up loving movies in general, Broadfoot became inspired as an adolescent when he watched behind-the-scenes documentaries about The Lord of the Rings. They “opened up a world of possibilities” about the many types of jobs one could pursue in the film industry.

By early adulthood, Broadfoot had started his career as a runner working across various departments. His aspirations soon focused on one specific element of film production. “I’ve always been an avid photographer as a hobby,” Broadfoot explains, “so location work paired my hobby with my career. I also loved traveling, and slowly but surely, this felt like the right fit.”

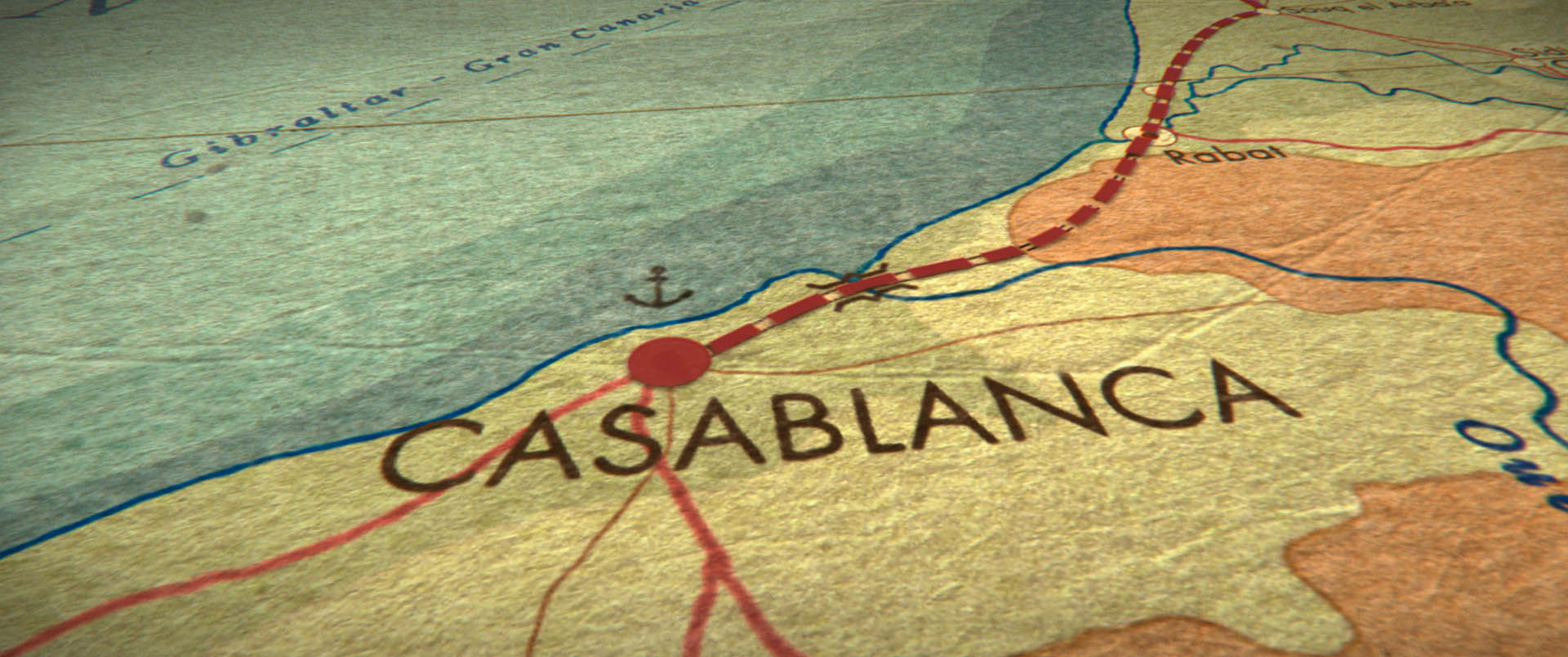

With experience ranging from Star Wars to more than a few Marvel epics, Broadfoot was no stranger to big movies. But Indiana Jones brings its own unique standard. “The famous graphic of the Indiana Jones franchise is that red line going across the map,” he notes. “It sort of weaves its way through everything. The locations themselves are integral to the stories. Indy is an explorer, so there’s a requirement to have him travel to places fitting for him. It was a challenge that I relished, but it was a little daunting as well. We had to keep up a certain standard.”

Broadfoot joined the Indy team in the fall of 2021. The start of production was still months away. “The film had been around in various guises already,” he says, “so there had already been some scouting and research done. But the script had evolved and we were looking in new directions. It was a good time to join, but it was at the tail end of Covid, which did have its own challenges.”

In the initial phase of his role as supervising location manager, Broadfoot oversaw a team of scouts in multiples countries, each helping to identify potential filming sites based on descriptions in the screenplay and on briefs from director James Mangold and production designer Adam Stockhausen. Where a typical Indy adventure already demands a large global search for distinct locales, Dial of Destiny faced additional challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Any travels in foreign countries resulted in weeks lost to quarantine,” explains Broadfoot. “Sometimes it’d be 10 days quarantine in the country and then ten days upon their return. So we tried a new remote scouting technology for the first time. Essentially, we had a team on the ground with an iPhone camera. The footage they captured went through an app and was beamed back to our control room in the UK, kind of like a broadcast scenario. Then that was fed into a Zoom call. The director in Los Angeles, the designer in New York, and the producers in London could be on the same call with a high-definition link to real-time footage of the location. They could speak to us and direct the camera around the location. We could even move between different countries and teams on the same call. We were limiting the traveling of the team so there was less exposure to COVID and less time in quarantine.”

Having narrowed down their selections, a small team would then visit the locations in person. “There is definitely value in being there in person to settle on what the final location is going to be,” says Broadfoot. “In every scenario, we established that we were in the right place and it was worth visiting. When we traveled there, we quite often wandered elsewhere and found other options as well.”

But there were other unique challenges. The film’s memorable tuk-tuk chase was initially slated for India. But when Broadfoot and others traveled to the cities Jaisalmer and Jaipur, “there was a terrible outbreak of Covid, and we had to leave the country and reevaluate,” as he explains. “Katmandu in Nepal was considered next, but then a similar Covid outbreak happened. Morocco came together very quickly after that.”

Dial of Destiny ultimately brought the cast and crew to dozens of locations in six countries. Once the sites are chosen, Broadfoot and his team transition into coordinating roles, overseeing local permissions and logistics. “We had multiple teams in England, Scotland, Sicily, and Morocco,” he explains. “We also had visual effects shoots in Austria and New York. Each country requires a large team for a project of this scale. The location managers and assistant location managers handle permissions and oversea the direct interface with the public or property owners. They’re also assisted by a dedicated floor team who take care of the more practical elements of filming. Another crucial role are the location office coordinators, who are the heartbeat of the department. They’re not only dealing with the mountains of paperwork, but are looking after the welfare of what can be quite a large team.”

England’s Pinewood Studios was homebase with its large soundstages. Elsewhere in the United Kingdom, Bamburgh Castle in Northumberland and the Leaderfoot Viaduct in the Scottish borderlands were used to film scenes in the prologue set during Indy and Basil’s adventure in World War II. Another British location was the Scottish city of Glasgow, standing in for 1960s New York City.

“I’m from Glasgow, so it was quite special to film there,” Broadfoot says. “I’d never filmed anything in my hometown before, and we shot in the city center for two weeks. It was dressed to be 1960s New York, including the moon landing parade. There was a real buzz in the city. In the evening, the public would come down to see the set dressing. It was a spectacle and a great experience.”

As Broadfoot points out, the city’s appearance stands in well for American cities like New York, Boston, or San Francisco. “It’s primarily Victorian architecture, built from red or blonde sandstone,” he explains. “The streets and city center are laid out in a grid system, which is similar to most US cities. Glasgow City Council also offers a huge support for filming. You can do things in the city center that you can’t do in London or many other cities. There’s only a handful of cities in the UK that enable those levels of control.” He humorously adds that during the two weeks of filming in his hometown, Glasgow was uncharacteristically sunny.

Apart from the United Kingdom, Sicily featured the greatest number of filming locations. The screenplay had specifically noted the Ear of Dionysius for the large cave where Indy and Helena enter Archimedes’ Tomb. “It’s a limestone cave, and its name comes from the fact that it’s shaped like a human ear,” Broadfoot explains. “This was the first thing that drew us to Sicily. We also needed an archaeological temple site, and Sicily is loaded with these types of things. We visited many of them, and once we had located both the Segesta Temple and the Ear, we realized we could get most of what we needed there.”

“When we were scouting Sicily, the portrayal of the final act was still in development,” Broadfoot continues. “We stumbled upon the Tonnara del Secco, which is an abandoned tuna factory on the coast. It’s got these magnificent walls around it. Adam fell in love with it, and envisaged extending these walls and having Syracuse behind it. That was the first incarnation of how that could be shown. The location was a pleasant surprise. It helped us show ancient Syracuse in a realistic manner.”

While the main unit worked in Sicily, second unit began shooting the tuk-tuk chase in Morocco. “It’s scripted as Tangier in the movie, but it was actually shot in Fez,” Broadfoot explains. “When the main unit completed in Sicily, we joined the second unit there for the tuk-tuk elements with the principal cast members. There were a few pick-ups back in London after that, but the majority of work was done after Morocco.”

Overall, Broadfoot enjoyed the multi-faceted challenges of Dial of Destiny’s story, not least of all the mix of different historical periods. “We had three main time zones in this film — technically four,” he points out. “There was the 1944 stuff during World War II, which was fascinating in its own way. Then we had the modern-day 1960s. We had the ancient Syracuse stuff. Three completely different time periods. And then the scene at Basil’s house is a flashback to the 1950s, so there are actually four.”

Having grown up in Scotland, Broadfoot spent years living in London and now makes his home in Croatia. He credits his job for fueling his love of world travel. “I’ve been living a nomadic lifestyle and have been traveling for work over the last 10 to 15 years,” he concludes. “It’s been a good way to see the world. I love to imbed myself in the local community, working and living with local people. It’s an authentic experience, and when I leave a place, I feel that I know it well. I’m lucky that way.”

Lucasfilm | Timeless stories. Innovative storytelling.