John Lewis: Good Trouble: An Interview with Filmmaker Dawn Porter

In Collaboration with Skywalker Sound, the Documentary Tells an Essential Story

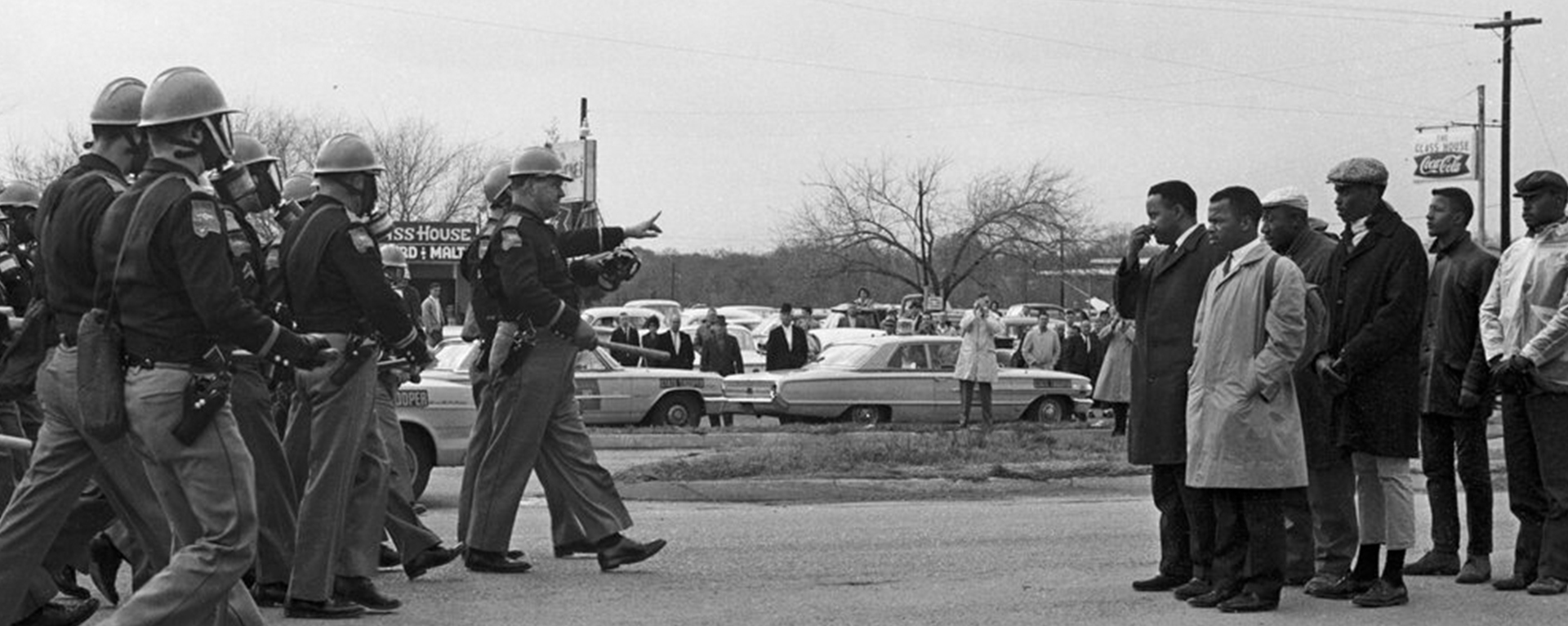

In 2020, award-winning documentary filmmaker Dawn Porter released her new film John Lewis: Good Trouble, the story of the late Congressman and Civil Rights icon. In celebration of Black History Month, Porter recently chatted with Lucasfilm’s film development coordinator Erin Hill for a virtual discussion about her career, collaborating with Skywalker Sound, and the power of this increasingly relevant story.

Erin Hill: Congratulations on directing and producing John Lewis: Good Trouble, and The Way I See It. I loved that movie this year as well. I know that you started out as a lawyer. Now you have 13 films in your pocket that you’ve directed and you’ve produced even more. How did you make that jump and what was the thing that made you feel confident that you were able to transition like that?

Dawn Porter: I would not say I was confident [laughs]. I would say, I was interested. I kind of moved slowly in the direction of directing. Starting as a lawyer, as a litigator, you really are a storyteller. You’re trying to take something that’s complicated and make it comprehensible to a lay audience. So the skills for being a lawyer, the kind of lawyer I was, and being a documentary director are really complimentary.

During my time as a lawyer, I took countless depositions, which means that you have to listen to people. I think for all directing, the most underrated skill is listening. Instead of directing somebody I think of myself as kind of uncovering the story that’s there from the person who’s the protagonist. But to be more mechanical about it – I went from a lawyer at a firm to in-house at ABC. And I moved then to the journalism side, where I worked for ABC News doing ethics and standards. And in that job, my role as the lawyer was not to say “what can you legally do,” it was “what should you do.”

When you start thinking about the ethics of storytelling you really start thinking about what’s necessary to tell the story without being exploitative. What does this story need to be told fully and honestly? What does it need to know to be true? From there, once you get in the groove of doing that and finding that heart of a story, it was really easy for me to say, “I could do this with things I come up with,” rather than doing it for other people and helping them find their way to their story.

But, to tell you the truth, I didn’t call myself a director – I hadn’t been to film school, I hadn’t done any of those kinds of traditional paths. Really until my first film was finished. And even when I was making it, to tell you the truth, I didn’t have a, “Oh, this is going to be a film in a festival.” I didn’t have that vision for it – I just really wanted to tell the story of these young public defenders with pictures and images. So I just kind of went one step at a time and then, as the film started getting developed, the steps kind of started to reveal themselves to what was possible for it. But I didn’t start out with a grand hope of, “This is going to be a whole new thing,” [laughs] it just kind of kept going, naturally.

EH: What was that moment, when you did feel comfortable calling yourself a director?

DP: The real moment was Sundance – the premiere of Gideon’s Army. I remember the lights went down and everyone was quiet, anticipating the film, and I felt my face getting hot, and I thought, “This was a terrible mistake.” [laughs] If this is a failure it’s going to be on such a huge stage. So, then when it was received well, I felt, “Okay, yeah, I really did this.” By the way, when I say “I” it’s a “royal we” kind of situation, because nobody makes a film by themselves. It’s really, in the best circumstances, a beautiful collaboration among people who are all contributing bits and pieces, so it’s very hard to put the “I” in film. It’s very much a “we.” And I can say that confidently now, knowing what I bring to it. But also knowing the people I collaborate with and how important they are to the film and to me.

That actually brings us to Skywalker [Sound] because Skywalker and the mixers that I’ve worked with have been such an integral part – I mean that so sincerely. It never occurred to me how much fun their music and sound mix was going to be until I got in that room. And they really encouraged me to say out loud what I wanted and to not be embarrassed about asking for things. And I think that’s a really important lesson for filmmakers who either are just starting out, or are a little quieter. Say what’s in your head – in English. You don’t have to know all the technical terms for things. What I would express to your people – to Chris in particular – is, “This is the feeling I want from something, and how can we then get there?” It’s like a dance, and it’s very satisfying when you’re able to communicate that to a partner who can then bring it to life.

EH: And you’re talking about Chris Barnett from Skywalker Sound?

DP: I’m talking about Chris Barnett, and Pete Horner. Those are the two mixers. I’ve worked more with Chris – I love Pete, but I’ve worked more with Chris. I think what he’s helped me to do is develop a language for speaking not only with the Skywalker team, but also with the composers. Because now I carry all of that information. I know that if we don’t have these options we’re not going to be able to make or do the things we want to do in the mix and in the sound design. I’ve just learned so much and it’s been really fun. Plus, Chris in particular is the most honest critic. He’s like, “That was good, that was good.” [laughs]

EH: For a filmmaker who’s looking to potentially work with Skywalker Sound, can you tell us about how you were introduced to them? I’m also curious to know, throughout the pandemic and having to do things remotely, how you were able to build off of that relationship and keep things going?

DP: Yeah so the real story is the year before getting Gideon’s Army, my first film – the year before it premiered at Sundance. The editor Matt Hamachek – who’s just directed his first film about Tiger [Woods] for HBO – Matt and I went to Sundance the year before we had a film there just to see films and network with people. And the true story is once upon a time there was a whiskey tasting party at Sundance that Matt and my husband went to and he came back and he was really excited. And he said, “I met the Skywalker guys and they would love to hear what we’re up to with this movie.”

So it kind of happened at a Sundance whiskey bar to tell you the truth. But then, we wrote to them – and the reason we had to write to them – you could clearly just call your people and say, “Hey I have this movie, and this is what we’re doing,” but we didn’t have enough money. But Skywalker was really leaning in to working with documentaries. I don’t know if this is still the case, but the way it was described to me is it was almost a gift to the sound design team, because a lot of documentaries are quiet. And so the sound really just shines through, and it’s such a crucial element, and people like Chris and Pete, they understand that so intuitively well that everything they do is going to be heard exquisitely and expressively. So they really worked with us on our budget to make sure that we could get that kind of attention to it. And that’s a great investment in a relationship, because now I’ve been back several times and the budgets of the things I’m working on are larger. So that relationship is really, really important. And I will say that even though we were certainly one of the smaller budget projects – I think we were next to the equivalent of Tron 19 or something. But what I really appreciated is how they did not make us feel like a small project. We got a beautiful suite, we got muffins, we got the full attention of our team and appreciation of the team – we got a parking space! It was very clear to us that everybody there cares about every project. If you put that name Skywalker Sound on it, they’re going to make sure that it delivers to that standard of quality. And I have felt that with every single project that I have brought there, which I think is really saying something for how much the people who are doing the work there care about the work. They’re not just paying attention to the famous rich people. [laughs]

EH: Was John Lewis a subject that you pursued developing on your own or was it something that was presented to you?

DP: I had done a four-part series for Netflix called Bobby Kennedy For President, and John Lewis appeared in that series, and he gave a really emotional and fantastic interview for us that really elevated the four episodes. So CNN came to me, and this was after they’d had a lot of success with RBG, and I tease that they were looking for another 80-year-old to highlight, so they came to me. But they just said, “What would you do with it?” And so I came back with a pitch that the thing about John Lewis was to take him out of the past and bring him into the present. Most people thought of him in terms of his civil rights activity, but he had been in Congress for so many decades and had been taking all of that civil rights energy into the present and was still such a powerful voice, so I really wanted to show how his past influenced his present. So that’s how that came about, and by then I had mixed Gideon’s Army at Skywalker, Bobby Kennedy, which is four episodes, Trapped – so, by the time I got to John Lewis, it was about seven projects, working with basically the same people, and when you have that relationship it certainly pays off anytime that you have a working understanding and you know how the other person works, and you know what they need to do their best work.

Where that really paid off, was in the pandemic, because I was on the east coast, so I couldn’t travel out there. And because we’d worked together so many times before, Chris just knew a bunch of things that we would normally go through and say, “Do you want this, do you want that,” or, “I’ll just do the usual, right?” So he did a first pass that was exactly what I would do, so we could really focus remotely on the particular details. I don’t really know how he did this, but somehow through Apple TV we were able to communicate in real time, so it was almost like being in the room together. But I will say I really miss being in the room. It’s such a gift to be able to be without interruption, just focused on your work on a big screen with someone who’s going minute by minute on your movie and making sure it’s everything it should be. I mean, it’s just such a special experience.

EH: You mentioned tackling Bobby Kennedy before. But even with John Lewis, did you feel any pressure about documenting him?

DP: Oh yeah. [laughs] I mean here was a civil rights icon, and John Lewis is a person who a lot of people think they know, but there was so much more to his life. He told us so many stories. He told a story about organizing a rally for Bobby Kennedy that occurred, unfortunately, on the day that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed. I didn’t know that it was John Lewis who had organized for Bobby Kennedy to be in Indianapolis that day. It was a young John Lewis, who said to Bobby Kennedy, “You must continue with this speech.” A lot of Kennedy’s other aides are saying it’s too dangerous, but it was a 20-something-year-old John Lewis who led to Kennedy telling that Black audience that King had died. And many people think that’s one of Kennedy’s finest moments, and that’s directly because of his relationship with John Lewis. You know, when you hear stories like that you think, “There’s so much more to the Congressman than people knew.”

That’s what I was excited about exploring with him. The other thing is – and I didn’t know how important this would be – I wanted to do something while he was living. I wanted to do something, where I could ask him the questions I wanted to ask him. And, of course, as we all know, he passed away soon after the movie was released, which was a total shock. I mean he was fine during our whole production – he was the energizer bunny. So it was so bittersweet – he did get to see the movie, but it was really bittersweet because I always expected to be traveling the country with him and letting everybody else see that side of John Lewis that we saw. So we are really grateful to have the film experience, even if we didn’t have the second part of it, which is him seeing all the love that came back to him after people experienced the film.

EH: And how did the experience of the life of the film change after his passing – did that put stress on you, being personally tied to this part of his legacy?

DP: Yeah, it really did. I had never had the experience of knowing somebody famous who passed away like that, personally. The weekend that he died, it was all over the news, his face was everywhere, his voice was everywhere – I’d get in my car and it was on the radio, I’d get home and it was on the news, his funeral was televised. And I had just spent a year traveling with him and seeing all of his funny little peculiarities, and seeing how funny he was. He was so gracious and generous to our team. One thing that I think about a lot now – he never once asked what was in the movie. He never asked. He would say, “How are you?” but he wouldn’t say, “How’s it going? What do you think?” We’d just say, “Oh, Mr. Lewis, can we see you at the next place and he’d say, “Yes!” He was confident that it was all going to be fine. And when somebody puts that much trust in you – I’d say the pressure was on me, you know? I wanted to live up to that trust that he had.

EH: Someone I was very happy to see interviewed in the documentary is Reverend James Lawson. He was my pastor growing up at church, so I’ve just felt very blessed to have learned so much from him, and every time I have been able to hear him speak it’s a privilege. I don’t feel like he gets the attention it deserves.

DP: I know that!

EH: Yes. He started non-violent workshops in Nashville and became a mentor to the leaders who are emerging at the time, like Mr. Lewis and Diane Nash.

DP: And King.

EH: Yes, and partner with them. He was someone who is mentoring people who we see as leaders now. So, were there any other people that would come up in conversations with Mr. Lewis, who he looked up to?

DP: The people that he looked up to the most were certainly Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King and Jim Lawson. I mean, those were people who were equally formative in his life.

Lawson leading him to study Gandhi, and to study non-violence and the history of other leaders – that was incredibly important for John Lewis, and for Bernard Lafayette, and for so many others like Diane Nash. They were very, very influenced by him. I think what was different about the teaching of Reverend Lawson and Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is that they encouraged their young people to study. They weren’t just saying, “Do what I do” or, “Do what I say,” they were saying, “Go read, and let’s talk about it, let’s talk about what these ideas mean.”

That method of learning has you interpret the messages in a very personal way. It’s, “What do these teachings mean to you, how do you interpret God’s command?” So, for John Lewis, accepting a philosophy of non-violence was almost religious. It was, “This is how I should live my life. This is my understanding of how God commands me to be as a person.” And, if that’s the case, you don’t have any other choice because it’s literally synonymous with who you are. But you don’t get that understanding if it’s foisted upon you, you get it through your own understanding and what speaks to you.

I think that was very powerful for me to think about – and to also separate, and highlight, and point out how intentional John Lewis’s philosophy was. It was like he had been baptized again at the age of 19 when he went through that process of studying and learning, and then he just never looked back. There’s a line in the film where Bernard Lafayette is talking about the civil rights leaders, and he said, “We had changed, and once we had changed it was over, they could not go back.” Once they’ve seen what they felt was the truth, they couldn’t live any other way. So, if you understand that you understand why they would risk their lives, because they felt like that was the true expression of the lives they wanted to have.

EH: Optimism seemed like such a central part of his work and his effectiveness, and I felt like that was a tone that you used in the movie. And there’s not a lot of focus on setbacks that he has throughout his career as an elected official later on. But I thought the most poignant moment was the relationship that he had with Julian Bond. Seeing that interview shortly after Julian loses the election was just remarkable. Seeing them side by side, seeing winner and loser side by side – something I can’t imagine seeing now – and then Bond’s explanation of why he lost was that Bond carried the Black vote 60-40 and Mr. Lewis won the white vote 80-20. We don’t really get a reaction from John Lewis about that. We don’t really see the impact that it brought on him, but we know that there is one. Did you ever hear him address that relationship?

DP: I asked him 90 ways till Sunday to speak more about that [laughs]. One thing with older people is – and I think this is really true of older Black people – is they’re just not going to answer what they don’t want to answer. I do think if you know Mr. Lewis – and at this point in the film you start to know him a little bit – he takes the blow that Julian delivered with that very intentional strike, which is, “Our people chose me.” But you also see that he doesn’t let that detract from his acceptance of the win. And he’s a really good meditator in some ways. He’s able to take something, depersonalize it, and kind of watch it go and say, “That’s not the core of who I am.” But I’m sure that comment stung in particular. And Julian Bond was very bitter at that point.

Seeing that footage – first of all, John Lewis did not really dwell on setbacks. He had some periods of depression after King died, after Bobby Kennedy died. He was quite shaken after he was dethroned as the leader of SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] and lost to Stokely Carmichael. He was upset, but what he would do over the course of his life was turn his attention to what he could do rather than what he wasn’t able to do. He was quite a pragmatist, in some ways, which is if everybody in SNCC is saying we have to be violent, I can’t be violent, there is no way forward here. So that’s not the best use of my energy, where is a good use for my energy? I’m not going to leave the movement, but where can I most be of service?

I think I didn’t dwell on it in the film because he didn’t really dwell on things. Which doesn’t mean he didn’t feel them; he’s just very focused and a very steadfast and determined person. But the thing that I actually love about the exchange with Julian Bond is that there’s this mythology that everyone who’s for civil rights has a unified approach, and believes there’s only one path to progress, and that there’s no dissension within the communities. Which is a very myopic and kind of infantilizing exercise – to say, “All Black people think the same thing, they all think there’s one way to progress.” That’s just not true. There’s lots of conflict within a movement, and out of conflict hopefully comes progress. I liked showing that internal behind the scenes conflict. I also liked that exchange because one thing we don’t often think about for John Lewis is his ambition. And ambition is often described in such a negative way, but if he hadn’t had ambition, he wouldn’t have become a civil rights leader, he wouldn’t have left his farm in Alabama, he certainly would not have become Member of Congress and head of a powerful Ways and Means [Committee]. Ambition led to all those things. So are there side effects to that ambition? Absolutely, but being nuanced about how you think about it, I think is important in seeing John Lewis for just a moment in terms of his ambition. I think it’s important to understand that’s also part of who he was.

EH: You get to see that clip of Tom Brokaw asking him about becoming a bureaucrat and then saying, “Not to use that dirty word” or something like that. And I found that so fascinating because I don’t think anyone would ever ask that question today – I hope – as if it’s offensive to somehow delegitimize yourself as an activist by actually becoming a lawmaker.

DP: And that is that is still a conversation that’s happening now, right? We have Cori Bush, an activist in St. Louis who is now a member of Congress, Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, you could even say Reverend Senator Warnock and Senator Ossoff have both come out of a much more activist tradition. And when you think about that, John Lewis really paved the way for those folks to say, “No, there is a way to fight from within the establishment and it’s important that our voices are inside as well as outside.” But there’s also a shift that has to happen – when you’re an activist, you can agree not to compromise. When you’re a legislator your job is all compromise, so how do you withstand the criticism that could come from your community if you’re not of singular focus? I think John Lewis paved a way for people coming behind him to say it is possible to navigate those waters effectively – to be true to myself, to be true to my constituents, but also to work effectively as a member of Congress.

EH: Yes, I was so glad that you focus on his long list of legislation that he has passed and authored. I feel like sometimes he is confined to being a civil rights icon or somewhat of a single party politician.

DP: I completely agree, and I’m so glad you’re saying that because that was a real goal of mine. Also to gently ask the question – we know that he’s done all these things, why do we insist on putting him in a box that’s like a postage stamp? Because if you’re a legislator – I wanted to focus on the strategy that he and the other civil rights workers utilized in order to achieve what they achieve. They weren’t just brave with their bodies. They were strategists. It took strategy to become the first city in America to desegregate in more than 100 years. That took a strategy that they devised, they implemented, and they executed. So why don’t we think of John Lewis as a brilliant strategic personality? And I think that could come back to race – he’s much less threatening if you see him as a kindly grandfather who put his body in the way, in kind of this noble way, instead of a fierce politician, which is what he actually always was. So for him, it was not that much of a leap to go to Congress. He’d been navigating the halls of power since he was 19. Now he was just doing it from a different perch.

EH: I love all of the CNN films – yours are my favorite now – what kind of resources does that relationship offer you, and is it cohesive fully with your vision?

DP: Yeah – like I said, nobody makes a film by themselves. You have partners, either in your financiers, in your crew, in this case in your broadcaster. I have known the editorial team – Amy Entelis, Courtney Sexton, and Alexandra Hannibal – for a long time kind of casually. I worked with Amy at ABC News. So I have a lot of respect for those women and how they approach films.

You don’t always like notes, but when you respect the people who are giving them, you understand that they are given for the benefit of the film. So you may not always agree with different notes, but it really does make a difference when you understand that the people are trying to make it the best film that it can be. So I think there’s just kind of a mutual respect, so they were trying to make sure that we could get to where we wanted with the film and have it be the film we wanted it to be. And I want to be a good partner, I want everybody to see it on CNN. And to understand that they keep delivering these unexpected and beautiful and lyrical movies – it’s not an accident. They’re working to cultivate filmmakers, to push them to be able to deliver that. I think of the Apollo movie or RBG – there is starting to be a CNN style of documentary that’s really extraordinary.

EH: Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me about this. I’m just so delighted to get to meet you. Thank you.

DP: Thank you! That was super fun, thank you for such insightful and close watching. That was not the cliff notes version of an interview! You really watched.

EH: Well I’m sure you were aware of John Lewis before you started documenting him. He’s someone who I have watched for a long time and learned from so I’m just really happy that he’s been part of the national conversation more and more. It’s important that we don’t lose sight of how he started out and the sacrifices it took to get there, and how the work continues

DP: Absolutely, I agree one hundred percent.